Understanding GDP

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a measure of the market value of all final goods and services produced in a specific country over a specified time period. It isn’t intended to capture all economic activity, or reflect changes to living standards. This video provides a good explanation:

Note, however, that the video misses the word “final” in the defintion, and considers the coffee machine to be part of GDP. In fact, GDP is only concerned with goods sold to consumers.

GDP is expressed either in nominal and or in real terms. The classical dichotomy is the technical term for the idea that nominal variables and real variables can be analysed separately. The table below provides some examples of each type:

| Real variables – Quantities and relative prices | Nominal variables – Expressed in money terms |

| – Real GDP – Capital stock – Real wages – Real interest rate | – Money supply – Price level – Inflation – Wages – Nominal GDP |

This is a good explanation of the difference between nominal and real GDP:

What is a recession?

Traditionally, a recession has been defined as two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth. The main problem with this is that sometimes we have very severe economic shocks that recover within 6 months (e.g. Covid), and at other times a sequence of low growth that may or may not dip into negative territory is not as much of a concern as a sharp contraction. In the US a recession is determined by the NBER based on the following:

“a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months”

NBER

Recently, the Financial Times has adopted this approach as well.

Economists are often accused of knowing the price of everything but the value of nothing. And we shouldn’t imply that GDP is everything. David Henderson uses the term GDP fetishism for when people judge a policy based only on whether it increases GDP, without considering how it impacts living standards. We can list several reasons why GDP diverges from living standards, and can be a bad measure to target:

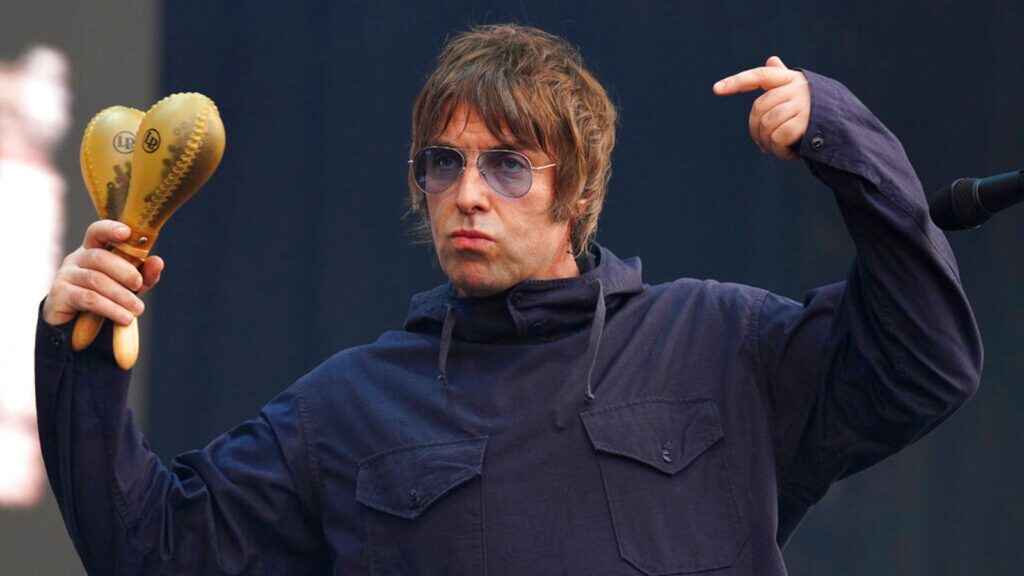

GDP only measures output that is traded, but not all “work” ends up on the market. In 2013 former Oasis front man Liam Gallagher split from his wife, and began dating his personal assistant. If they got married, ceteris paribus, GDP would fall. This is because as his employee the value of her labour is counted in GDP figures. But were they to marry, and have a different contractual arrangement for their relationship, presumably she would stop receiving a wage. Previously traded labour would become untraded. The same amount of is work being done, but GDP falls.

When slaves were emancipated in the US South they reduced the amount of labour they supplied by one third. GDP fell, because the measured value of their production was lower. But their well-being was clearly higher.

Because they don’t sell goods and services on the open market we can’t measure the value created by government. But it is plausible that at least some government production is worth less than it costs.

In Turkmenistan there is a large monument with a 39-foot gold- plated statue of former leader Saparmurat Niyazov that rotates throughout the day so that he’s always facing the sun. These types of project have little economic value, in which case measured GDP overestimates well-being.

There is a great joke that when an earthquake hit Blackpool, on the northwest coast of England, it caused £500,000 worth of improvements. Ordinarily though when a natural disaster strikes welfare falls. Although this isn’t captured in GDP figures, the costs of rebuilding will be part of measured output. If a hurricane destroys a pier, and it later gets rebuilt, GDP figures will treat this as a gain. But you’re back where you started. You aren’t any better off. In fact, you’re worse off, because you had to commit scarce resources to rebuilding the pier, rather than investing in other projects.

The neglect of opportunity costs is known as the “broken window fallacy”, which originates from Frédéric Bastiat. He tells a parable of a boy who breaks his father’s shop window, and receives a scolding. However, a crowd forms and someone asks what would become of the glaziers if no windows were ever broken? The locals celebrated the increase in economic activity. The problem, as Bastiat points out, is that the gain to the glazier is only the seen effect. To an untrained eye it may look as though the creation of work is a good thing, and indeed GDP figures would support this view. But we should also consider the unseen. Namely the goods that the glazier would have bought, if he hadn’t needed to replace his window. The reduced income of the tailor is less tangible, but just as important, as the increased income of the glazier.

If you chop down some trees and sell them for paper, this will help to boost economic activity. But once all the trees are gone, you’re out of resources. In many environmental situations, bad institutions mean that there’s an incentive to deplete resources at the expense of the long run. This is encouraged by the fact that GDP figures will be presenting such depletion as “growth”.

What’s included in GDP?

Try out this interactive tool from Marginal Revolution University

The best example of the harm that can follow when countries promote GDP growth beyond other factors is the Soviet Union. And yet remarkably, much of their growth was an illusion that fooled Western intellectuals.

How economics textbooks got growth wrong

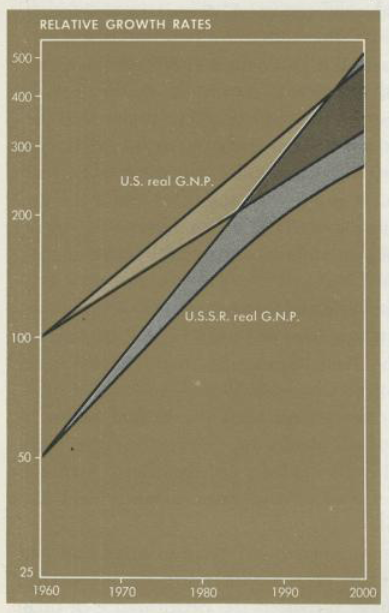

This chart was used in a best-selling economics textbook, written by Campbell McConnell and published in 1963. As you can see, the USSR were deemed to have half the real income level of the United States, but was projected to grow at a much faster rate (around 2-3x).

McConnell thought that the USSR could overtake the US as early as the mid 1980s.

Indeed in every new edition of the textbook, published after 1963, USSR growth was projected to be faster than the US. And yet even in the 1990 edition the US starting position was still twice as high as the USSR.

This was a remarkable failure to notice what was going on – much Soviet growth was an illusion, but many Western intellectuals failed to notice.

Simon Kuznets was the pioneer of national income accounting, and famously said:

“the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income.”

Simon Kuznets

But just because GDP isn’t everything doesn’t mean it’s nothing. In 2025 the Trump administration floated the idea of removing government spending from GDP to get a more accurate depiction of the state of the economy. But not only does this measure already exist, it misunderstands how GDP is computed. I recommend this article: GDP is a good measure. Don’t mess with it for political reasons.

Here are Diane Coyle’s thoughts on the usefulness of GDP:

Hans Rosling has said that “There is no single indicator through which we can measure the progress of a nation”. But income per person correlates with, and leads to, a lot of the things that we really do care about. So let’s not dispense with GDP entirely.